[For info on my upcoming events and tours, scroll down to the end of this article -Liam]

The entire country is on the verge of a panic attack. It feels like everything could come crumbling down any moment. Anxiety levels are so high that crawling into a hole in the ground is starting to sound like a good option. No, I’m not talking about 2025. This pervasive sense of foreboding dread describes the fear of nuclear annihilation that gripped America at the height of the Cold War.

President Truman’s decision to vaporize two Japanese cities in 1945, and the horrifying aftermath of that destruction, ushered in a new chapter for mankind. Unlocking the secrets of the atom suddenly meant that human extinction was a real possible outcome of warfare. Once the Soviet Union began testing their own nukes in 1949, any doubt about the USA’s vulnerability vanished. Under the doctrine of MAD (mutually assured destruction), the only thing keeping us safe was the knowledge that both sides were staring down the barrel of an apocalyptic arsenal. The hope that our enemies (or one of our own rogue generals) wouldn’t be foolish or careless enough to trigger armageddon provided little solace to the generation of children trained to hide under their school desks in the event of incoming warheads.

Despite the grim prospect of living in a world ravaged by radioactive fallout, political leaders and civilians alike quickly decided that desks alone wouldn’t provide sufficient protection from mushroom clouds, so the nation got to work constructing shelters. Considering that people have been seeking safety in underground spaces since the earliest cave dwellers, this reaction is unsurprising. Whether the potential enemy is a saber-toothed tiger or an intercontinental ballistic missile, the impulse to burrow in response to danger seems deeply ingrained, a genetic urge that sends us scurrying back to earth’s bosom when faced with existential threats. Or maybe, aside from an aptitude for thermonuclear physics and a few other distinguishing traits, humans aren’t as different from rodents and bugs as we’d like to believe.

I hadn’t given much consideration to the topic until a few months ago, when I saw that an amateur civil defense historian had posted a Google Map titled “Fallout Shelters in Oakland California” to the Oakland subreddit. I connected with the map’s creator, Haley Radford, and learned that because she lives in Fresno, most of her research was conducted virtually, using online archives like Newspapers.org and Google Street View. I was intrigued by the idea of finding some long lost shelter, picturing a life-sized time capsule filled with midcentury rations, anti-communist propaganda, and bulky electronics. So I decided to build on Radford’s research by digging into the history of this mostly forgotten infrastructure.

I started my exploration with a visit to Oakland’s first privately-built bomb shelter, an above-ground bunker constructed in 1950 by an eccentric inventor on the grounds of his apartment complex in a quiet, residential neighborhood near Peralta Hacienda. According to Oakland Wiki, Clifford McCaslin “came up with the idea after talking to two of his tenants who had survived the blitz of London during WWII in a similar shelter.” McCaslin later told the Oakland Tribune that “they laughed and laughed down at City Hall when I applied for a building permit for this shelter,” but after the start of the Korean War in June 1950, his idea caught on. “By the summer of 1951, bomb shelters appeared at the Home Show at the Oakland Expo, and were common in real estate listings,” wrote Peter Hartlaub in a 2019 San Francisco Chronicle article.

The complex where McCaslin built his shelter is now known as Humboldt Gardens and the property has changed hands several times over the decades, but a longtime resident named Janeen agreed to give me a tour. Since McCaslin’s era, the shelter has been used as a music room and a wine cellar, but now it’s the current landlord’s storage space, so I wasn’t able to look inside. Still, it was worth a visit to see this architectural anomaly, which looks like a smaller, DIY version of Berkeley’s freakish Enclave Apartments, due to its Frankensteinian mishmash of styles. What appears to be a conventional cinder block rectangle from the front is revealed as a hallucinatory monstrosity from the side. The vine-covered bricks are crooked, appear to be melting, and are topped with something that may or may not be the skeletal remains of a Polynesian-themed patio umbrella that McCaslin built on the bunker’s roof at the behest of his wife.

Spread across the structure’s exterior are engravings that range from logistical (“Well water available; inside pumps. Area, 550 sq. ft.”) to smug (“To plan is human; to fulfill is divine”). Fortunately, due to a lack of aerial bombardments, McCaslin never got the opportunity to rule over this cramped kingdom, which he built large enough to have room for his tenants. Despite occasional geopolitical flare-ups, like 1962’s Cuban Missile Crisis, the residential bomb shelter concept didn’t gain much traction in the Bay Area and the strange monument quietly tucked away in an East Oakland backyard seems to be one of the relatively few local bunkers still in existence.

A list published by the Oakland Tribune in 1962 (uncoincidentally around the same time as the aforementioned missile crisis) indicates that many fallout shelters were located in public buildings, such as schools, post offices, and administrative facilities. One of the most significant was located beneath the stage at Woodminster Amphitheater, a hillside venue surrounded by redwood trees in Joaquin Miller Park. “In 1958, Oakland officials built the Oakland Civil Defense Control Center to operate as a second City Hall if the downtown building were flattened by a Russian bomb,” Matthias Gafni reported in a 2017 East Bay Times article. “Inside the 14- to 24-inch thick concrete walls was a 60-kilowatt diesel generator, more than 30 days worth of fuel, water and food, 20 telephones, a kitchen, and a control room.”

On a gray February morning, I met Joel Schlader at the side entrance of Woodminster Amphitheater near a large sign declaring the chunky concrete structure to be an “Emergency Operations Center.” Shlader told me that his parents, former Broadway performers, had started producing musical theater at Woodminster starting in the mid-1960s and that he and his sister were now carrying on stewardship of the beloved community institution, which stages outdoor shows throughout the summer. As Joel led me down a staircase, through a series of locked doors, into the bunker’s bowels, I prepared myself to be transported back to the 1950s, but my visions of encountering a Cold War time capsule were quickly squelched. The place was trashed, damp, and it smelled like mold.

Industrial ovens sat rusting in the middle of a room; a row of water-logged cubicles had been gutted of their communications equipment; rotary phones, old car batteries, and broken glass littered the mushy carpet and dark hallways. Although a few closets still contained large drums full of water and cans of food rations, I learned that after the “Emergency Operations Center” shut down in the 1960s, the Oakland Police used the facility to run training scenarios up until the 1990s and apparently they didn’t take very good care of the place. Given the choice, I’d rather take my chances with radiation poisoning than spend a night in this cluttered dungeon.

After mentioning an attempted burglary in 2020, Joel told me that the City of Oakland has essentially abandoned responsibility for the space. Given a proper renovation, the former shelter could be converted into classrooms, practice spaces, offices for the educational groups that operate in Joaquin Miller Park or any number of productive uses, but sadly the possibility that our cash-strapped city would prioritize such a project is about as likely as Elon Musk joining the Peace Corps.

On my way out of the building, I noticed a sign dating back to the Ampitheater’s opening on March 5, 1941. Below the words “Woodminster - Cathedral of the Woods,” it said: “To inspire and advance the noblest aims of mankind.” A few months after that sign was erected, the US would be plunged into the deadliest war in history and our municipal resources then shifted away from building cathedrals of arts and culture in favor of weapons and places to hide from them. A handful of crumbling Nike missile sites, still jutting from ridgelines throughout the Bay Area, testify to this legacy of suicidal brinksmanship. Somewhat paradoxically, it was the heavy concentration of these military installations (and the nuclear bombs reportedly stored at the Concord Naval Weapons Base), intended to keep us safe from foreign attack, that would have made this region such a legitimate target for a WWIII first strike.

After my visit to the ruins of Oakland’s “Emergency Operations Center,” my search began sputtering out. Going down the list of former fallout shelters, I started cold-calling apartment building property managers, stores and government offices located at the addresses published by the Oakland Tribune in 1962. Oakland Unified School District’s communications director John Sasaki even reached out to four principals on my behalf to ask about shelters that had once existed at their schools. Nobody knew anything. Water barrels, food packets, chemical toilets, and all other traces of Cold War preparedness had evidently been removed long ago. The basements went back to being used for storage – or occasionally something more interesting (I was delighted to discover that the Breuner Building’s sub-level is home to a vast archive of historical resources curated by the California Genealogical Society.)

Losing hope that I might find a fully-stocked vintage shelter, I lowered my expectations and began hunting whatever traces remained of their existence. For obvious reasons, officials wanted the public to be well aware of shelter locations, so galvanized steel signs bearing a distinctive triangular logo along with the words “fallout shelter” were often affixed to appropriate buildings and utility poles. After finding some leads about fallout shelter signs near Lake Merritt that had been photographed recently, I visited the sites (a defunct elementary school and an apartment building) only to find that the signs had vanished, possibly swiped by collectors to be sold on eBay.

Feeling discouraged, but not ready to give up yet, I trudged over to the last lead on my list: A social services administration building that was shut down by Alameda County in 2019. Despite being on a prime stretch of Broadway, plans to redevelop the site, and several adjoining parcels formerly owned by the county, into mixed-use residential have stalled. The fenced-off complex has been sitting vacant for more than half a decade, yet another dead zone in downtown Oakland awaiting a shift in the economic tides.

As soon as I turned the corner from Broadway onto 4th Street, I saw the rust-colored FALLOUT SHELTER sign still screwed into the building, about 15 feet off the ground. Carefully stepping around someone sleeping on the sidewalk, I approached the building to take a picture. Within a few seconds, a security guard emerged from behind a gate to ask out what I was doing. I told him about my research and as soon as he realized I wasn’t there to vandalize anything, he lightened up. He told me his name was Willie and he seemed relieved to have someone around to break up the monotony of sitting in an empty parking lot.

All I had to do was ask him one question about the building he was guarding and he opened up about his frustration with the state of Oakland. He told me that he didn’t understand why the building was going to be torn down when it seemed perfectly fine. He said that when he was growing up in Oakland, there were no encampments of unhoused people. This middle-aged Black man looked like he was almost about to cry when he asked “Why is this building empty?” while looking at the person sleeping on the sidewalk. It wasn’t really a question, so I just nodded. “You’ve gotta take care of your people, man,” he said. “You’ve gotta take care of your people.”

As I was walking away from the abandoned social services building, it dawned on me that fallout shelters didn’t really go away after the Cold War, they just got rebranded. Instead of the government creating them in public places or people like Clifford McCaslin building one to serve his neighbors, it’s mostly billionaires and libertarian preppers digging “survival bunkers” to escape a collapsing society. The chances of waiting out the downfall of civilization in a glorified basement seems about as likely as surviving a nuclear war in one, but I suppose the idea of having a safe place to retreat at least provides a shred of hope. But where does that leave the rest of us?

East Bay Yesterday events, tours, and news

March 16 - Researching and Writing about History with Liam O’Donoghue (Details here)

March 25 - Oakland and “The Pacific Circuit”: Live podcast taping with Alexis Madrigal and Noni Session (Click for details and tickets - this will sell out fast!)

March 27 - Industrial East Bay: Exploring how big business shaped our region [KPFA fundraiser & podcast taping featuring Richard Walker] (Click for details and tickets)

March 28 - Street Spirit 30th anniversary event: Panel discussion on the legacy of community print media (Details and tickets coming soon, check my Linktree next week for more info)

Plus: Tickets are still available for my Oakland/Alameda history boat tours on March 22, April 12, and April 25. Check the FAQ page for more details on the route, logistics, etc.

Don’t forget to keep up with the East Bay Yesterday podcast. My most recent episode, recorded live at the former site of the California Cotton Mill with the Co-Founders crew, explored the history of Jingletown and much more.

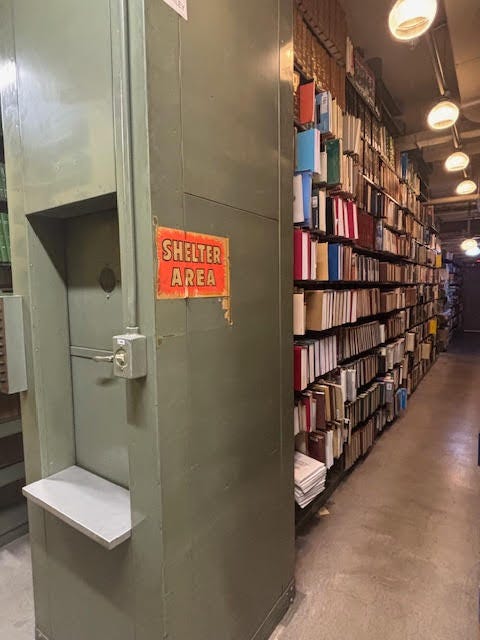

One final note on fallout shelters: During my research at the Oakland History Center, my librarian friend Erin Sanders informed me of a sign in the basement of the main branch that seems to date back to the Cold War era. Here it is…

Thanks for reading!

Liam